I started learning linear algebra a couple weeks ago. I’m taking a three-pronged approach to study:

Linear Algebra – David Lay

Lay’s book isn’t very heavy on theory and mostly covers matrix computations. I took an introductory course in Linear Algebra over a five-week period back in 2007, so I’ve already done most of the problems in this book. However, since the course was so short, naturally cramming was involved as I scrambled to cover the entire textbook in a little more than a month – so with respect to this I didn’t benefit from the spacing effect to commit the things I learned into long-term memory. I think a review would be helpful since my current job duties demand that I understand matrices well.

Introduction to Linear Algebra – Serge Lang

Serge Lang wrote an introductory text that is a little bit more theoretically rigorous than Lay’s book. This reading is pretty short at 280 pages, and contains a modest number of problems (328). I’m reading this mostly at a pretty slow pace (4 pages a day), so I should be done in about 2 months. This mainly serves as a supplementary text to Lay.

Sage

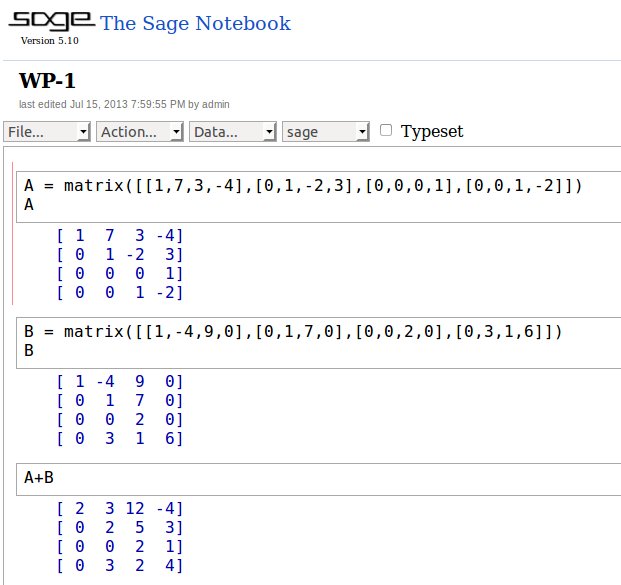

I wrote about Sage a couple years ago, and I’m finally putting it to use to help myself learn linear algebra. Sage is an open-source project aimed at creating a free, viable alternative to proprietary computer algebra systems such as Mathematica, Matlab, and Maple. I’m starting out by reading the Sage Tutorial and applying the built-in commands to the problems from Lay’s book. For example, here is a screenshot of the Sage Notebook:

Here, you can see three cells of code along with output for each one. The first cell contains two commands, one to declare a matrix A, and another to show it:

\[A=\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 7 & 3 & -4\\0 & 1 & -2 & 3 \\0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -2 \end{array} \right] \]

The second cell declares and prints matrix B:

\[B=\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & -4 & 9 & 0\\0 & 1 & 7 & 0\\0 & 0 & 2 & 0\\0 & 3 & 1 & 6 \end{array} \right] \]

The third cell adds the two matrices together:

\[A+B=\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 7 & 3 & -4\\0 & 1 & -2 & 3 \\0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & -2 \end{array} \right]+\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & -4 & 9 & 0\\0 & 1 & 7 & 0\\0 & 0 & 2 & 0\\0 & 3 & 1 & 6 \end{array} \right]=\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 2 & 3 & 12 & -4\\0 & 2 & 5 & 3\\0 & 0 & 2 & 1\\0 & 3 & 2 & 4 \end{array} \right]\]

Vector Addition

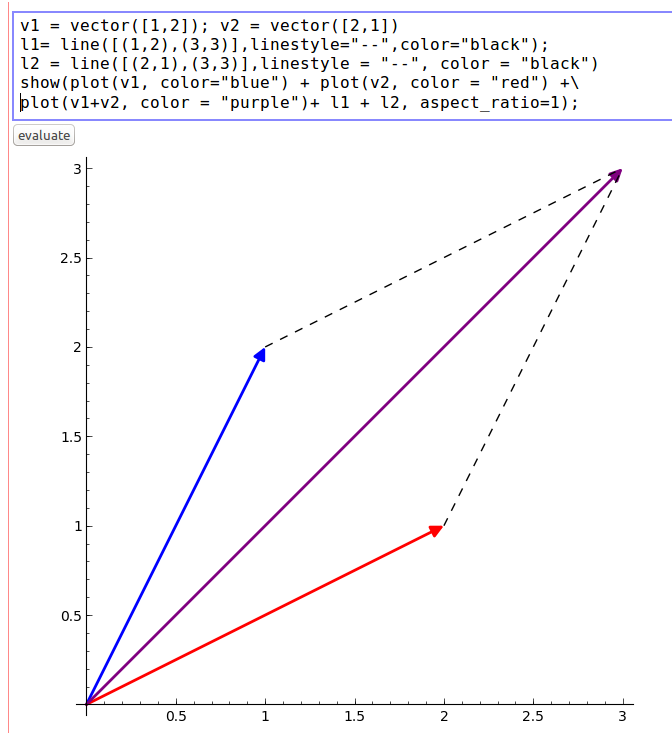

I really like Sage’s plotting capabilities. The following example declares two vectors, v1 and v2, and plots their sum, which is also a vector. v1 is blue, v2 is red, and the vector sum is purple:

I added some dashed lines (which are declared as l1 and l2 in the cell) to complete the parallelogram in the plot. This shows that the sum of two vectors can be represented as the fourth vertex of the parallelogram where the other three vertices are its component vectors and the origin.

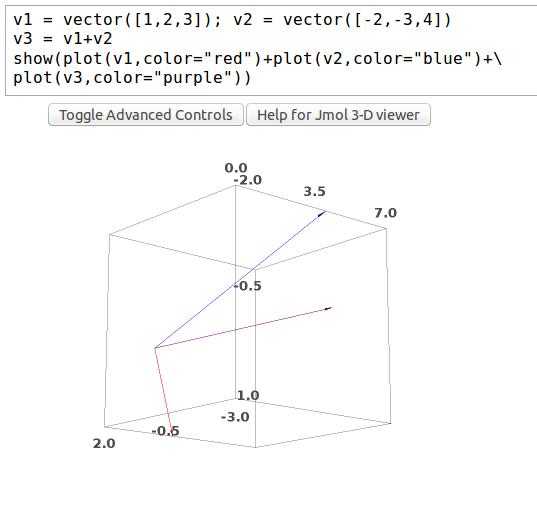

Sage also has 3D plotting capabilities. The following example shows the sum of two vectors in three-space along with its components: