Thirteen years ago, I wrote a post about injuries that I sustained in college, which led me to stop performing music for over a decade. I am happy to report that yesterday, after so many years away from the stage, I gave my first public performance since 2008 at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston. The path back to performance hasn’t been easy – my hands never got better, and by now the tendons on my thumb, index, and pinky fingers on both hands have continued to loosen over the years and have now detached from the knuckles and move around laterally between the grooves of my fingers, making it difficult for me to coordinate the movement of my fingers. At the beginning of this year, the pain became so unbearable that I finally took action to deal with the issue. After receiving guidance from my piano teacher, as well as treatment from medical professionals, I have been able to regain the ability to play music, and to do the things I used to enjoy. I wanted to spend the time reflecting on how I got here, and perhaps give guidance to anyone else suffering from a similar situation.

How I got involved with music

Like every other Asian-American kid, I started piano lessons at an early age, although I don’t quite remember when. I was maybe around six years old and I had little choice in the matter. While I did have the desire to play, since I had been listening to my older sister, there was never any kind of discussion with my parents about what instrument I wanted to play or whether I even wanted to pursue music at all. I only remember that one day I found myself in front of a piano in my teacher’s apartment, learning how to play with my sister. I couldn’t have been taking lessons for more than a year though, since they ended almost as soon as they began, with no explanation from my parents as to why they stopped taking me. I wasn’t exactly raised in the kind of environment that encouraged me to speak out about what I wanted in life so I never asked them any questions about it or made any requests to go back. And frankly, I didn’t really enjoy practicing, so I didn’t complain. At that age I hadn’t yet made the mental connection between practice and performance.

Fast-forward to age 12, I remember having to choose what kind of music I wanted to pursue in middle school. I wanted to be like my sister, who played cello in the string orchestra, but not exactly like her, so I picked viola. I liked how it had the same notes as the cello but it was smaller, and how not a lot of people picked it, so it made me feel unique to have played it. I remember the day I walked into the orchestra room the summer before school started to rent my first viola. My teacher, Kevin Black, was there, and I was so excited to have been lent what was probably the shittiest 3/4-sized violin with viola strings attached in the entire school. But I didn’t care. If it weren’t for cheap $50 rental fee, or even the very existence of the school orchestra, I wasn’t sure if my parents would have let me play at all.

I took to the instrument immediately and I wanted to get better. But trying to get my parents to understand the importance of private lessons was an uphill struggle. At age 12 I was already late to the game in pursuing this kind of thing and I had watched my sister trying to learn on her own without the help of a professional. I believe that if she, being musically inclined, had gotten the right lessons from the get-go, she could have really gone somewhere with the instrument. But, if she couldn’t get lessons, how would I? Somehow, after a year of playing without a private teacher, I was able to get my own teacher and started to improve rapidly, placing well at the regional competitions for 7th and 8th graders. I had a hard time growing up in school, but despite that, music was always there for me. It was my favorite thing. I knew that no matter what crazy stuff was going on in my social or domestic life, nothing could take it away from me…as long as I had the ability to play.

At some point before high school, I was told by my teacher that someone else would be taking over my instruction. I was never given an explanation but I never questioned it since his other students had to do the same. But I never got along with my next teacher, as he didn’t seem to be emotionally invested in my growth as a musician. What made matters worse was that my dad lost his job when I was in 10th grade, so we cut lessons to every other week to save money. After having lackluster results at regionals and failing to make state, I began to get frustrated, and was looking for a better teacher.

It was maybe around high school that I started to realize how far behind I was – the more competitive students had started earlier, had better teachers, better instruments, and most importantly – practiced more. At the beginning of 11th grade, I started lessons with Larry Wheeler, a viola professor at the University of Houston. Up until then, I really had no idea what I was getting myself into. All I had access to were whatever Suzuki books I could find at the local violin shop or in the storage closet in the school’s orchestra room. Mr. Wheeler introduced me more serious elements of viola study, and encouraged me to participate in the Greater Houston Youth Orchestra, where I encountered very talented students, many of whom are now professional musicians. It was at this time that my progress skyrocketed. I performed well at my last year of regionals and (barely) made state orchestra, a goal I had set out for myself when I first took lessons with Mr. Wheeler. Before that, I considered it beyond my league, but it was he who convinced me that I had it in me so I made one last attempt to make it before graduating.

Participating in state opened up a whole new world for me when it came to musicianship. I encountered some very, very serious musicians and their teachers at the annual convention in San Antonio, TX. There were kids with thirty to forty thousand dollar instruments, practicing 5-8 hours a day, who were bound for the top music schools in the nation. While I felt like an amateur in their presence, for the most part I was just happy to be there, since I had made it much further than I had imagined I would at that point in time. It really opened my mind to learn how far kids would go to get their foot in the door of a winner-take all industry where the opportunities to make good money are very slim. But more importantly, the experience introduced me to works of music I never would have imagined. It was the first time I had watched a group of teenagers perform an entire symphony from the beginning to the end – it was Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5. Most high school orchestras, even the best ones in the nation, will only play one movement from a symphony and even then, they might spend an entire year preparing for it. While I knew I wasn’t going to make it in the world of professional music, I knew this was something I wanted to do – to play a symphony like this, someday.

Oddly enough I would do just that a few months later at Alice Pratt Brown Hall for GHYO at Rice University. It was Beethoven’s 7th Symphony (although I faked most of it) and one of my favorite concerts. It would be the last time I would perform with many of the violists I grew up with and became friends with in the community. It was funny too, I had to fill in for one of the lower orchestras. At first I refused, because I had just given blood the day prior and was a bit weak, but my director, Bryan Buffaloe told me that I was full of shit and to get on stage. If you’re reading this Mr. Buffaloe (or Bryan, I’m old enough to call you that now), I wasn’t lying, I really did give blood, seriously!

The onset of injury

I began having symptoms of what would turn out to be a permanent condition when I was around 15 years old. I had awoken from a nap one day and my fingers locked up. I knew at the time that something wasn’t normal, but out of fear I never asked my parents to take me to the doctor. My dad for one, was very difficult to approach about these things and I remember him throwing a fit when I broke my arm, telling me to just stop pretending until my mother finally took me to the emergency room. I feel like deep down he was scared, that had we not been living in the world of modern medicine, that I wouldn’t have survived. So I better learn how to make do without these conveniences, in case we wind up without them.

Anyway, at the beginning it wasn’t so bad. I wasn’t in pain, my fingers just wouldn’t move for the first few minutes in the morning, but once they loosened up I could play normally, so I didn’t tell my teacher about it either, although I wish I had, because maybe he would have been able to direct me to somebody who could help.

When I arrived at college at the University of Texas at Austin, it was kind of like the time I started high school. I had an unimpressive audition and wound up in the middle of the pack in the viola section in the university orchestra. I was still determined to keep exploring music, so I participated in chamber music groups as well as the opera, in addition to the orchestra. It was here that I began performing more substantial works of music, from full symphonies like Beethoven’s 5th to entire operas like Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro. I would spend maybe 3-4 hours a day practicing in one of the school’s 100 practice rooms and browse the world class music library, increasingly building up my exposure to composers and pieces I had never heard before. During my time there, I continued private instruction with Michalis Koutsoupides and Ames Asbell. I was having a blast, telling myself I wouldn’t wind up in middle age telling my kids that I used to play, but hadn’t played in 20 years…

But as my junior year approached, my symptoms continued to worsen. I began feeling pain, and by the winter of 2008, I had lost so much coordination that I could barely grip a pen. It was a miracle I was able to complete my studies. I gave one last performance – a quintet in one of my school’s chamber clubs. At this time I did tell my parents about this, and visited a few hand surgeons and several specialists to find out what was going on. It was never determined, and still now doctors don’t really know what’s wrong. All advised against surgery, as they said things would recur if I got it – eventually my tendons would loosen up more and the problems would recur. Lacking transportation or really any experience in navigating the US health system, I had no idea what to do. And so I gave up, and wrote a final post about music in 2009 and didn’t touch an instrument again for a decade.

Other pursuits, my return to music, and reinjury

Rather than rage at the unfairness of the world, I was determined to keep living a full life, so I spent the next few years pursuing a various things seriously. I relearned how to write by letting my pen rest on my fingers while moving my shoulders. I had joined the college cycling team and participated in clubs and amateur races for a few years, doing strength training at the gym using the stronglifts program, and also learned how to program computers. I made a lot of friends doing these things and was, for the most part, happy. I wound up moving to Chicago where my social life improved significantly, and I got married. By the late 2010s I was feeling well enough to maybe start dabbling with music again. I could have done so sooner, but I was absorbed in my job, personal life, and these other activities. I purchased a digital piano and started playing a little bit but not seriously since I still had to finish my actuarial exams. Once I passed my exams, I decided to put more effort in to piano. I’m not sure what drew me to piano, rather than returning to viola. I think there is some practical aspect in apartment living that prevents me from spending a lot of time on an acoustic instrument, or maybe I was just tired of never getting to play the melody of anything. But something always drew me to piano. I’ve accompanied some inspiring performances, like when my classmate Darwin Weng played a movement of Grieg’s piano concerto or when I was in the orchestra for Poulenc’s double piano concerto, that made me wish I had never stopped. Every practice room at the university had a piano in it, and there was just something in me that told me I would regret life if I never picked it up again, so in January of 2021, I reached out online to Cheryl Stone to help me find a teacher in the Chicago area, one who had experience with musicians with physical disabilities. She recommended Dr. Daniel Baer at the Music Institute of Chicago, who helped her overcome her own physical issues.

However, with the pandemic in full swing and having been confined to a 450 sq. ft. studio apartment with my wife, my physical health began to take a toll. While it was nice to not have a respiratory illness or be dead from covid during quarantine, the lack of exercise, and the accompanying lack of boundaries as far as managing my time between coding, work, and practice led me to one day writhe in excruciating pain upon typing the first few keystrokes at work. This led me to finally seek treatment for my hands. Unfortunately, the piano lessons would have to end before they really began, but Daniel said he’d be there pick up when I was ready, and that he was confident that we would be able to get through this.

Recovery

I had read in a few news articles that the late Dr. Alice Brandfonbrener, who is considered to be a pioneer in treating musicians, had founded a performing arts medicine center in Chicago, and that it was just a few blocks away from where I lived. Her legacy has now been absorbed into the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, and I began occupational therapy as well as physical therapy at a local clinic. My OT taught me various grip, posture, and dexterity exercises to improve my fine motor control and to correct various muscle imbalances that she observed.

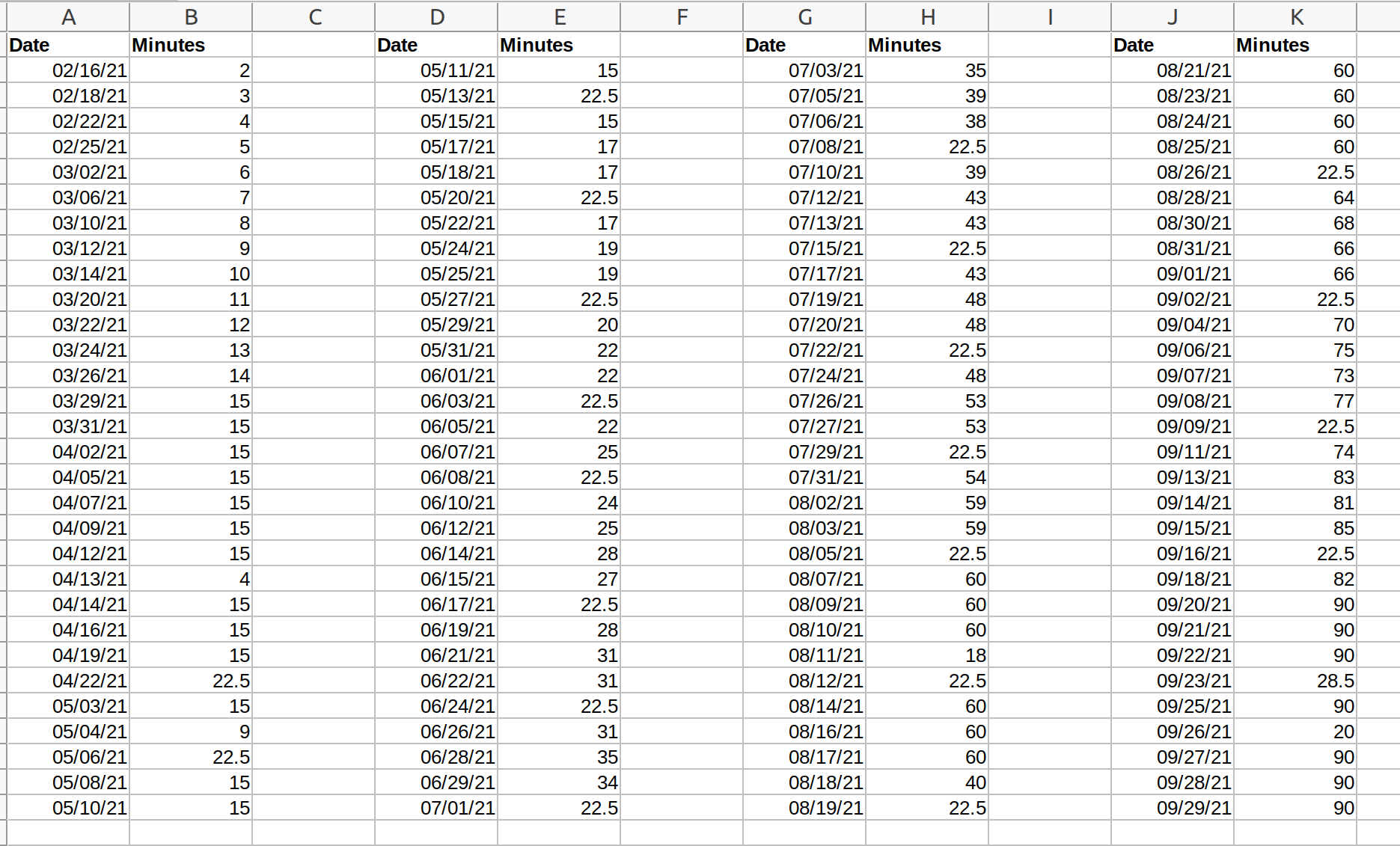

Once the pain subsided, I began to practice piano again. Daniel told me under no circumstances were I to exceed 15 minutes, and to stop mid-phrase should I reach that point. I started at just 2 minutes for a session, playing just the first measure of Purcell’s minuet. I set a strict schedule for myself not to exceed a 10% increase in playing time and, over the course of two months, worked my way over the up to 15 minutes and held it there until Daniel was ready to begin lessons. He told me that we would learn how to recruit the larger muscle groups of the upper arm, shoulders, back, and torso, so I could rely less on actively using my fingers. Over the course of 8 months I gradually increased my practice time to 90 minutes a day.

At first, progress was painfully slow, and nonlinear. At the beginning, the lessons were longer than my entire week’s worth of practice. I would have a 45 minute lesson, followed by 2 or 3 days of just playing 4 measures of music. It seemed crazy at the time, but I wanted to make sure I did things right when I started again. Sometimes weeks, the pain would return and I wanted to quit. Oftentimes, I didn’t know if my condition had gotten better or worse. During my days of doing pretty much nothing, I would read books like What Every Pianist Needs to Know About the Body and Playing Less Hurt. I thought I had tried everything, including some fringe mindbody theories by Dr. John Sarno, where I’d do these long journaling sessions trying to trigger repressed emotions (maybe it was in my head, after all). But I kept persisting, and with the support of Daniel, the OT/PT medical staff and a mental coach, I finally made it to practicing consistently for 90 minutes to 2 hours daily, without pain.

Recital

Three weeks ago Daniel asked me if I was interested in doing an in-person recital for adult students. It would be the MIC’s first set of in-person recitals in two years. I was hesitant at first but I had a few pieces ready, so I was willing to do it. I prepared two pieces, a minuet by Purcell and Melody by Aram Khachaturian. While I could play these confidently on my digital piano, I was less certain on how they would sound on an acoustic piano. Unlike people who play string instruments, pianists must learn how to quickly adjust to performing on pianos that aren’t theirs. Within the first few seconds of their performance, they need to be able to guage what the piano can and can’t do, and adapt accordingly. Daniel said we’d spend the week leading up to the recital learning how to play on an acoustic instrument.

When I arrived at the MIC for my first in person lesson with Dr. Baer, I played on an acoustic grand. The action was much stiffer than mine, but with a more sensitive pedal. Some of the notes didn’t sound and the reverb was heavy. We talked about partial pedaling, but with just 3 days left to go before the recital, I was getting anxious on being able to incorporate it into my performance.

Over the next two days I rented a studio on the 9th floor at the Fine Arts Building in downtown Chicago. It’s an old building, with elevators that still have a human operator. On Friday, when I practiced, I could hear a very good orchestra rehearse Shostakovich 5, as the timpani in the 4th movement was immediately recognizable. It triggered memories not only of the time I heard the state orchestra in 15 years ago, or when my sister’s orchestra, conducted by James Kidwell, performed the 4th movement – the very movement that inspired me as a young boy to do whatever I could to transition from playing in a string to a full orchestra. The piano’s action was again stiff, with a less nuanced pedal that was so creaky I thought I was going to break the piano. Each piano has its own quirks, I guess.

I returned again on Saturday, the day of my 34th birthday, this time the Chicago Youth Symphony was rehearsing on the floor below me, bringing back memories of my own days in GHYO. After practicing partial pedaling for 2 hours, I played through my program a few more times without mistakes until I thought I was ready.

However, right before my wife, Yu Chen, took me out to dinner, I thought I’d do a practice run on my digital, since I happened to be wearing a suit. My dress shoe, which I hadn’t pedaled with before, got stuck in the pedal box. Oh no, I better try this again tomorrow. On the day of my recital, I again practiced partial pedaling on my digital for 2 hours, this time wearing a dress shoe. When I finally got accustomed to using it, I made the trip with Yu Chen to the MIC building to practice on some more acoustic pianos – it turns out the place where my shoe gets stuck in the pedal box doesn’t exist on an acoustic – all that worry for nothing. But that didn’t ease my anxiety because each of these pianos had their own strengths and weaknesses that I wasn’t used to. After warming up for an hour, I concluded I would have to make do with whatever piano was on stage, even if it was old and creaky.

After I made my way to Nichols Concert Hall, I saw a well-maintained Steinway grand in the middle of the stage. My teacher told me it would be good, but I wasn’t expecting it to be like, Steinway good. I had never played on an instrument of that caliber, so I got excited…my first performance back. I was a little nervous, but not excessively so. I told myself I cared more about being there and making it through my performance than how well it went.

I looked at the program backstage, in the minutes before my performance and I got anxious. I felt like I had, by a large margin, the easiest set of music out of everyone and the least experienced musician there. Just a few minutes later, somebody would be performing Chopin’s Ballade in G Minor, an advanced piece I aspire to play one day. I was intimidated, but inspired at the same time. She was also a student of Dr. Baer, so maybe I’ll get there if I keep at it.

My time came up. I walked on stage and bowed to the audience. I began with the Purcell. For the most part it went smoothly, but the action was heavy so the last note didn’t sound when I landed my left hand, but it was pianissimo so nobody noticed anyway, unless they had the score. After pausing for a few seconds I began the Khachaturian. The action was nuanced, so I was able to carry out I had been practicing under Dr. Baer on not lifting up the left hand fingers above the sounding point – not something I was able to do with every piano. The first half went by without a mistake, the second half, with it’s celeste-like syncopation, would be my finale. Somewhere in there I messed up, big time. But my friend Yeng Miller-Cheng told me no matter what, to not lose the beat, and to keep going, and that nobody would notice as long as I do that. So I did, hoping the very next note I would land would be the right one. And it was! In a matter of seconds the performance was over. Applause. I made it back to the stage.

I’ve waited so long for this moment. I’m not pretending to be any good, I still have a long way to go. I don’t do this for a living, there are no more competitions, deadlines, or auditions to worry about. This is just me, a regular person, doing what I want to do, to enjoy the things I want to enjoy. I’m finally back, and I’m looking forward to everything there is to explore in music.